House Calls

Pandemic Psychiatry and How We’re All in This Together

I am a doctor.

Covid-19 came early for me, back when the virus was still 2019 n-CoV. Before Dr. Li Wenliang died. Months before much of the world retreated to the safety of home, where the virus couldn’t find them.

The alarm rang in Wuhan, and I prayed we would find no human-to-human transmission. But no, by the middle of January evidence mounted that people were infecting each other. Could it be contained locally? No, by the third week in January, cases were clearly identified outside China. That sealed it for me. It was unstoppable. Sometime in mid-to-late January, the inevitability of global pandemic dawned on me.

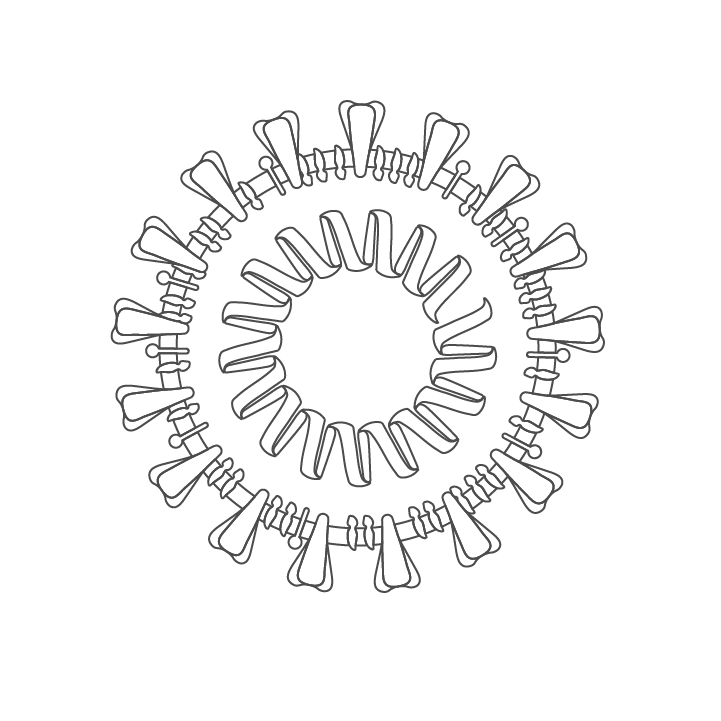

From that moment, the free flow of my attention changed. To this day it’s not yet back to its usual state. The coronavirus, later named SARS CoV-2 and its associated clinical illness Covid-19, became my constant companion. I envisioned the virus: a tiny unthinking piece of RNA surrounded by a lipid membrane and a bit of protein. Soulless, inanimate, indifferent to the outcome. But sometimes lethal nonetheless.

I stocked up on supplies, prepared to work by phone, FaceTime, Zoom. Friends and family started to hear my admonitions, as I became something like an inclement weather advisory. The message was not met with universal appreciation. Who would welcome such news?

As January bled into February, I became aware of the complexity of my role with my patients: addressing their ordinary concerns, their agendas in seeking help, but also asking myself what obligation I had to offer the information I possessed as a doctor and a human being, information that might help protect them from a danger unique in their lifetimes.

This question seemed to ask for a clinical decision, one for which no part of my professional experience as a psychiatrist and psychotherapist had prepared me. Distracted by my vision of what was about to unfold, I indulged a fantasy. I imagined disrupting the deep and sometimes quotidian process of listening and assisting with this message: “While I remain committed to your welfare and to the work we are doing together, I must interrupt to let you know that a viral disease of scope and mortality unprecedented in the lifetimes of almost everyone alive today, will strike us like a tsunami in a few short weeks, disrupting totally life as we knew it.”

Might this really be my duty? The tidal wave would arrive whether I were the messenger or not.

The whole idea seemed in stark opposition to my familiar role of helping people to understand that their anxieties often deviate from the realities they grapple with, help that can offer relief rather than to heighten anxiety. I pointed out to myself that I do not routinely remind my patients that thousands of nuclear warheads are pointed our way. That my role is specific, confined to assisting people with their mental health difficulties. I am a psychiatrist and not an all-purpose Mayday beacon.

And yet, if I smell smoke in the office, that's another matter...

In late February, but still before Covid-19 overwhelmed all of us in our beloved NYC, my reverie was disrupted by actual questions from my patients.

What about this virus? It started in China, and had begun to ravage Italy. Do we need to worry about this? Is it going to come here?

It’s amusing that I believed I was composed, measured even. And yet whatever my actual responses, a knotty exchange sometimes followed: You are always calm. You are the person who helps me to be less anxious. You seem anxious, so now I feel even more anxious than I felt before!

Did I say I was anxious? Maybe I didn’t have to. After all, whether or not I am a seasoned psychiatrist, skilled in maintaining boundaries between my life and my work, there was a reality before us. A plague was at the gates, and we were both well aware of the fact. Would an absence of apprehension make sense for anyone in such a situation?

How innocent these reflections feel in this new era of Zoom sessions and crumbling boundaries. My patients and I now look into each other's personal spaces, my shirt and tie ensemble long abandoned, an absurdity in my own home.

But much endures. Transference surely, perennial as the grass. Someone confides she is worried about me:

I can feel your anxiety.

Another feels the opposite:

Your confidence about an ultimate end to this situation buoys me up.

Perceptions like these mirror the parable of the Blind Men and the Elephant. A group of blind men are brought to an elephant, never before having encountered this unlikely creature. One touches the trunk and concludes an elephant is like a snake. Another touches the ear, and says an elephant is like a fan. Individual experience shapes the construction of reality. Someone touches one of my tusks, and finds I carry a spear; another my side and feels the durable wall that makes up my frame. My patients’ impressions of me and of the world may be altered by the current crisis. Examining these ideas and feelings continues nonetheless.

In early March, a patient tells me she is planning the trip of a lifetime, the wedding of her friend in South America later that month. Her excitement is clear, but so is her uncertainty. I decide to offer caution. We speak next in April and I learn she canceled the trip, despite friends who encouraged it. “I told them my psychiatrist would never want to worry me. You helped me have the strength to make the right decision.” Apparently it wasn’t the information I offered in itself that was determinative for her, but rather her trust in me.

China, Iran, Italy, and suddenly the vigil ends. In an instant, the wave that traveled inexorably from the other side of the world strikes hard upon our shores.

Sirens, endless sirens, herald the arrival. I am not there, but I hear them through my patients’ laptops and see them in their agitated faces. 5,000, 10,000, 15,000 deaths in the city.

I can do my work, maintain a professional disposition, but I can’t truly separate my personal catastrophe from those of all my patients. No one among us is spared. Grief, fear, compassion, desperation, determination...

My college buddy of 40 years is on a ventilator.

A dear friend loses both his parents within days.

My patient of decades cannot protect herself if she and her husband are to put food on the table. Her babysitter still comes to watch the three toddlers. All six get sick.

My 86 year old mother lives alone.

A respected colleague dies mere days after becoming symptomatic.

The father of my daughter’s best friend is intubated.

A patient in his mid-50s is out shopping when he calls for our meeting. He assures me he has no personal concern about Covid because he is in good health. I am firm and directive now: you really don’t want to get this virus, I say. He takes notice at last and thanks me. The next week we do not meet because he is sick.

I love my profession for its ceaseless variety. No two people have the same lives. The work is multiform; we all contain multitudes. But suddenly what was about many things has become about one thing and its consequences. Health and sickness. Managing this aberration. Isolation and its discontents. Some slip into severe anxiety, frank depression, even suicidal preoccupation.

I’m afraid I brought the virus in and it’s spreading through my whole house

Are you going out at all?

My husband has been hoarding his medicine. I’m afraid he needs to be in the hospital I’m attending a Zoom funeral for my friend

I can’t take this anymore

I hope you don’t know anyone who died

I look back at my fantasy of interrupting my psychotherapy meetings by sounding the alarm. Back then I was alone with the information, a doctor reflecting on disclosing to his patients a threat that had not yet intruded upon them. That potential discussion was a choice.

Now there is no choice. This is the discussion.

The virus hijacks not only the cells of the body, commanding them to produce nothing but virus. It also commandeers conversation, until the virus and its consequences become the conversation. So we talk about the virus after all, not by preference exactly, but because this is life at this peculiar, excruciating moment.

Under usual circumstances as I care for patients, my problems are not readily seen in the room. But during Covid-19, boundaries have shifted. Ordinary, safe, business-as-usual neutrality is impossible. We're all going through this. Everyone has their version; nobody is spared. I struggle. I cope with disaster. I miss loved ones and the former ease of sociality. I confront uncertainty. As do my patients. As do we all.

It is May. January is a world away now. At this moment, shared hardship and shared experience is undeniable. A pandemic by its nature affects everyone. The distinction between doctor and patient seems perceptibly altered. I am not present physically now. My patient has retreated to safety. From my socially distancing office, across an electronic link to my socially distancing patient, I feel a heightened sense of our common position: human beings enduring adversity. I am a doctor working for the wellbeing of my patient. But more than ever we are two people navigating the uncharted hardships of life together.

Bennett L. Solnick, MD is a psychiatrist in private practice in Manhattan and White Plains, New York